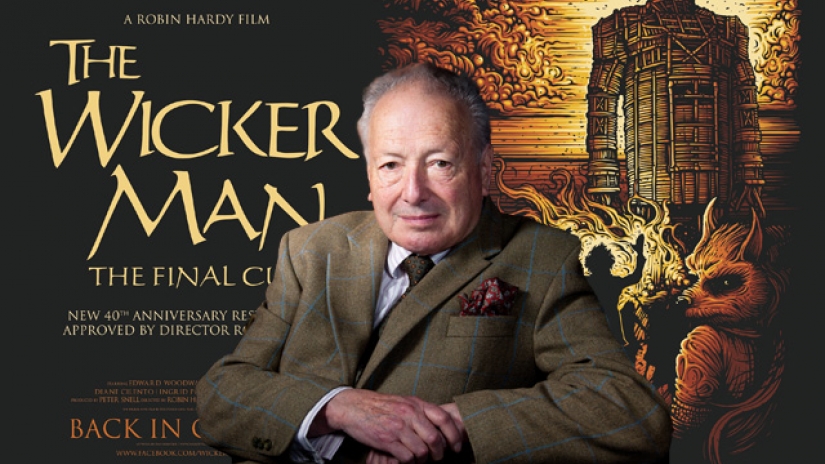

This Friday evening at Broadway Cinema, Nottingham, The Wicker Man’s octogenarian writer/director, Robin Hardy introduces his latest film, The Wicker Tree. The ‘spiritual sequel’ to the 1973 classic is being screened as part of Mayhem Horror Film Festival, which runs from Thursday 27 to Monday 31 October. We had a chat with Hardy to discuss the relationship between The Tree and The Man, why Hardy loves The West Wing and hates pigeonholing, and why he believes it’s far from grim up North.

Speaking to Robin Hardy is daunting. While Hardy’s voice is as beguiling as Britt Ekland’s dance in The Wicker Man, his back-catalogue of interviews fit into two distinct categories: meandering and evasive or engaging and informed. Fortunately, I’m speaking to The Latter Man.

The reason for our conversation is the imminent release of The Wicker Tree at film festivals across the UK; the film will not receive general release until May 2013. The Wicker Tree, broadly described as a re-imagining of its forefather, is based on Hardy’s 2006 novel, Cowboys for Christ. Whilst The Wicker Man is about a missing girl, The Wicker Tree is centred around a Texas pop-star-turned-gospel-singer, Beth, and her cowboy boyfriend, Steve. The pair go to Scotland to save souls. Understandably, early reviews have described is as a cover version of his 1973 classic. However, it’s a description with which Hardy feels uncomfortable: “The Wicker Man and The Wicker Tree are completely different films. There’s a different context: whilst The Wicker Man is set on an island, The Wicker Tree is set at the Scottish borders. Indeed, The Wicker Tree was influenced heavily by The Border Ridings. The event can be traced back over five hundred years when Scottish families would rob from the English. That anti-establishment theme is very important to the film. Clearly, there are similarities. In both films we look at a Scottish religious fabric which contains strong strands of paganism and an almost Dionysian commitment to revelry. And like The Wicker Man, I would like The Wicker Tree to be viewed, at least in part as homage to Scotland’s beauty. I have no problem with similarities being drawn there.”

The Wicker Man’s beauty almost never made it to screen. The tale is relatively straightforward: celibate Christian police sergeant Howie arrives on Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of twelve year old Rowan Morrison. Unbeknownst to Howie, the Pagan community have lured him there under false pretences. The journey from film set to film screen is, however, a little more involved. The film endured a faltering release schedule (it was originally released as a ‘B’ film to Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now); rights and ownership issues (the film was made by British Lion, a company bought during production by EMI); and released in at least four different cuts that were 86, 87, 96 and 99 minutes long. An alternative, upbeat ending was even suggested involving a dousing rain shower. Indeed, after a moderate reaction to its 1974 release, it wasn’t until 1977 that The Wicker Man truly caught fire. American film magazine Cinefantastique, in a commemorative issue, described it as ‘The Citizen Kane of Horror’. It’s a nom de plume for which Hardy has mixed emotions.

“I’ve always thought The Wicker Man was a film about beautiful songs and beautiful landscape, it’s most definitely not a horror film. If I was forced to pigeonhole the film, a process that I feel very uncomfortable with, it is a black comedy. I wanted the film to contain good jokes, a certain amount of sex – which is always cheering – but when it was described as ‘The Citizen Kane of Horror’, it became a horror by label, not intention. I understand the pigeonholing process: there’s plenty of space on Tesco shelves and the likes of horror films, but there is no black comedy section. I wanted The Wicker Man – and The Wicker Tree – to be beautiful, whimsical and comedic specifically to catch you at the end. For that reason, to call it a horror sort of misses the point.”

If there is horror in The Wicker Man’s (broiler alert!), it’s the burning to death of a devout Christian. Surely American religious bodies, never slow to be outraged, had something to say about that? Hardy noted: “Back in the seventies, Christopher Lee and I travelled around churches to discuss the film at Prayer Breakfasts. This was at the suggestion of some very, very bright students from New Orleans’ Tulane University – they had taken on promotion of the film. Today, Prayer Breakfasts are used by American politicians to forward their agenda. However, in the seventies it was used by religious groups. And, don’t you know, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Jews, Baptists, they all love talking about religion and were just delighted to be able to tackle this issue. Truly, we won them over. In fact, I think it’s fair to say that, in the US, the film was pretty much sold from the pulpit! The Christians especially loved talking about it. Well, to them, it pretty much explained the resurrection!”

For The Wicker Man, that’s about as much analysis with which Hardy feels comfortable. Analysis and debate continues to surrounds the film. In 2003, a Glasgow University conference dedicated to the work suggested the film critiqued Ludwig Wittgenstein’s contention that all civilisation is a thin veneer, hiding man’s animalistic intentions. To his credit, Hardy decries the film’s post-intellectualisation: “Look, I don’t think it’s the role of the film maker to be preachy, I think any points one makes should be as nuanced as possible. The most important thing is that it is a ripping good yarn. There are political points in the film but I find some of academia that surrounds The Wicker Man, frankly, amazing. I believe that it’s crucial that social commentary doesn’t get in the way of the film. If it’s a good story and a truly human experience all that other stuff will look after itself.”

At 82, Hardy has looked after himself. It would be difficult to describe his cinematic output as prolific. After 1973 The Wicker Man, in 1986, Hardy wrote and directed The Fantasist, the tale of an Irish woman who moves to Dublin and begins receiving phone calls from a stranger. Coincidentally, the city is being plagued by a serial killer who uses this method to lure his victims. Three years later, he co-wrote and produced Forbidden Sun a story of rape at a girl’s gymnastics school linked to ancient Cretan rituals.

Hardy has had plenty of time to catch a few films for himself; it’s hard not to wonder what he thinks of horror since The Wicker Man. Does he enjoy dark eighties sci-fi, modern Spanish, love-them-hate-them post-Scream slashers, or the incredible Korean wave? Hardy replied:

“In all honesty, the work I really enjoy is televisual. I think films are now short stories, I know that’s how I see my work. Don’t misunderstand me, it is the medium in which I work best and which I enjoy the most but I think the best, most inspiring work is now on television. The West Wing contains a just astonishing standard of writing. The Wire and Treme are similarly impressive and in the UK, I think Spooks is very good. The episodic format give you the chance to develop character in a way that cinema doesn’t allow. Personally, I wouldn’t want to be assigned a character to write as part of a collective, that’s not what I enjoy or am good at but you can’t deny it, the formula produces some incredible work.” (See, meandering, evasive, engaging and informed).

It’s difficult to know whether cinemagoers even want The Wicker Tree to be different from original The Wicker Man – the very least we can hope for an improvement on Nicholas Cage’s bemusing 2006 remake. Whether The Wicker Tree is a repeat, sequel, re-imagining or any other clumsily tacked-on label, let’s hope it doesn’t detract from the importance, impact or beauty of the original – truly, an incredible work in its own right.

The Wicker Tree will be screened at 7.45pm, Friday 28 October at Broadway with an introduction from Robin Hardy.

Leave a Reply